Blowing the whistle on environmental damage

His job is to clear fjords of past environmental sins and assist the police in their investigation of a reopened murder case. In his spare time, he documents the world’s climate history. Head of Section Bjørn Christian Kvisvik is proof that physical geography is a diverse – and necessary – concern in the 21st century.

He has his outdoor gear on today – he has just cycled to work at COWI’s office in Bergen. But the Gore-Tex trousers, fleece and trail shoes are often just as important at work as on the way there. Today, for example, he is going out to survey a disused farm. There he will scan the site with georadar to determine the number of buried animal carcasses under the ground – and the possible environmental impact on the local area. His day-to-day work is varied.

Bjørn Christian Kvisvik now works as Head of Section for one of COWI’s environmental departments. He started out as a physical geographer, but has also worked in several other fields within geology – everything from climate history to sediments, geology, glaciology and geochemistry.

“You can see a lot and gain a great overall understanding of nature through geology. You can see the whole history and learn to understand how weather systems and climate operate over time, and particularly what effect nature can have on society today,” he says.

And the last point is something that has especially interested him in recent years. Through what he describes as a sort of hobby and spare-time project, which is actually a PhD, he has gone particularly deeply into the climate of the past, and the historical development of the climate.

“I haven’t quite finished the project yet. As a Head of Section, my schedule is pretty full and it’s hard to find the time. But I have been on field trips to the Himalayas, Svalbard and Antarctica and gathered a lot of data.”

Arctic climate anxiety

He remembers one trip particularly well. It was to the old whaling island of South Georgia, southeast of the tip of Argentina and the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic. The island used to be known as one of the main bases for whaling. This happened after a Norwegian established the first shore station for modern whaling in the Antarctic, where Norwegian sailors lived and worked in newly-built settlements for over 50 years. Now there are no longer any permanent inhabitants on the island – apart from the animals and a British research station. Today, 2.5 million fur seals and 300,000 southern elephant seals breed on the island, and 2.7 million pairs of macaroni penguins and 400,000 pairs of king penguins nest there.

And that was where, working with other researchers from the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research and Bergen University, between elephant seals and Alpine peaks, he took core samples from lakes and mapped the geology of the area, focusing on the influence of the glaciers.

“We are using the data we collected to help to analyse the climate history there. I particularly remember when we came to examine a glacier based on a picture from 1980. When we got there, the whole glacier was gone. The areas near the poles, like South Georgia, are extremely sensitive to change, so we have to find out what is triggering these changes. Some are natural changes, but what we are seeing now are also very rapid shifts. And these show up very strongly in the Arctic areas,” he explains.

The areas near the poles, like South Georgia, are extremely sensitive to change, so we have to find out what is triggering these changes.

It is easy to identify with the idea of “climate anxiety” when you see the changes close up like this. But Bjørn Christian is not too worried about how the climate changes we are seeing will affect us in little old Norway.

“In Norway we are very privileged. We have many different climate zones, with high mountains and elevated land-areas, and we have very few low-lying areas that are seriously exposed to the effects of climate change. So the Norwegian nation viewed in isolation has less to worry about than many others. Nevertheless, much of our unique character will disappear when the glaciers melt, a lot of our biodiversity goes, and many alien species come in. We also face challenges from microplastics and pesticides and pollution from medical waste and environmental toxins. The uncertainties surrounding the impact of these are worrying. However, some of our fish stocks could well move south, so they will probably be OK.”

He smiles to acknowledge that it doesn’t sound like a dream scenario here at home either. Nor does he want to sound political. But once the facts are there on the table, it’s hard to put them back in the drawer. Moreover, when he takes his Norwegian glasses off and looks at the global situation, optimism is perhaps even further away. Out there in the world, especially in the Arctic regions and the Global South, the problems they face are of quite a different magnitude.

“When the permafrost melts in the Arctic, there is not much we can do to prevent the coastal strip from being eroded and whole villages having to move. People will have to migrate to find new areas to settle in.”

But enough of that; physical geography is more than just climate anxiety.

Helping the police with a reopened murder case

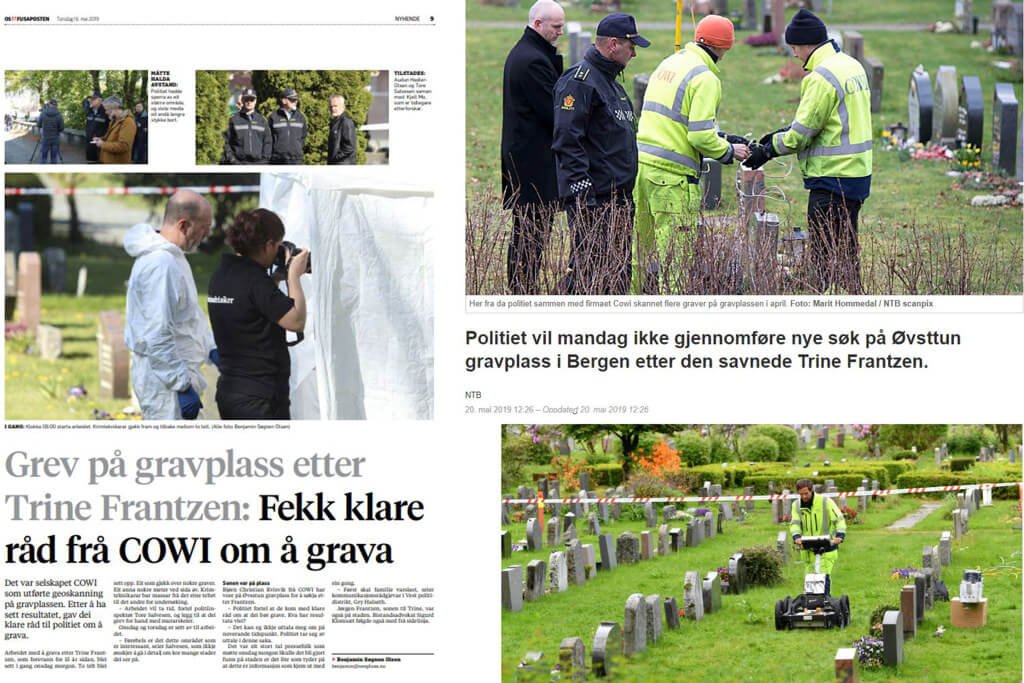

For the last six months, his mind has been on a different project. When the police received a new tip-off about a closed murder case from 15 years ago, it was suggested that the victim might be buried in an existing grave in Øvsttun cemetery in Bergen.

COWI was brought in to scan selected plots with georadar to see whether they could detect any anomalies under the ground there. An abnormality is an irregularity that could indicate something under the surface other than just soil. Together with a colleague from Denmark, they took detailed 3D scans of the ground. The technology is the same as that used when secret burial chambers and hidden rooms were located in the Egyptian pyramids and when archaeologists found traces of old Viking ships.

The scans enabled the police to prioritise the graves to be examined more closely.

“The results from scanning with georadar are not perfect, but the anomalies we find in the images can help us to see elements that do not fit. But these irregularities may also be clay, gravel or other features. We were open with the police about the uncertainty around our finds and what they can and cannot tell us,” says Bjørn Christian.

From industry to living city

He is not originally from Bergen, the city where he has been gradually settling down since 1998. But there is no doubt that Bergen has changed a lot since he drove in for the first time just over 20 years ago.

“When I moved to Bergan in 1998, I took a wrong turn and ended up in a dead-end street with burnt-out cars, right next to where COWI’s office in Bergen is now. Now the edges of the fjord around the town are quite different. At COWI we have done a lot of work to clean up the seas and harbour areas of Bergen in recent years. Such a long industrial history leaves its mark. You could generally say that these are leftovers from a time when environmental standards were not what they are today.”

Shipyards, dentists’ surgeries, paint factories, tanneries, waste from furnaces and roads, flaked-off house paint – to name just a few – have left the Bergen fjords full of environmental toxins. COWI is helping to survey and remove these pollutants. Puddefjorden has already been cleared, and the next fjord out is Store Lungegårdsvann, followed by Vågen (the inner harbour).

The preliminary results on the new clean seabed in Puddefjorden look good, and underwater photos show that fish, crabs and lobsters have settled well in their new surroundings. One small beach also opened recently along Puddefjorden, with more on the way. Swimming was not a very attractive proposition around here just a few years ago.

“It is fun to be able to contribute something so positive to the local area. It is really exciting to see such a social benefit. Now I am looking forward to three more years with the ‘Cleaner Seas in Bergen’ project, where we are acting as consultants to the municipality of Bergen and working to produce a cleaner seabed and good living conditions along the fjord.”

A privilege to develop capable colleagues

He does not work alone. As a section head, he is responsible for ensuring that 20 staff in the environmental department are happy in their work He has been in the job for less than a year.

“It is incredibly nice to be so close to people and to try to develop them and realise their potential. It is also a privilege – we have the best people working here and we have to make sure they don’t work too hard. It is a technically very talented group, they find it fun to work and could almost go on working indefinitely because they enjoy their jobs.”

And he thinks that looking after people is the best recipe for a successful business. He remembers what he heard when he came for a job interview at COWI in 2013.

“The person who interviewed me, a wise man in the field, said that if you can offer technically exciting projects and a good working environment, business will go well too. I took that with me as my philosophy.”

Get in contact

Bjørn Christian Kvisvik

Head of Section

Environment, Norway

Tel:

+47 416 67 693

bckv@cowi.com